The Unseen Battleground: Navigating Crime and Privacy in the Crypto-Enabled Metaverse

The emergence of virtual reality (VR) and the expansive metaverse promises a future of immersive experiences, decentralized economies, and unprecedented digital connection. Yet, beneath this exciting facade lies a rapidly evolving landscape fraught with privacy risks and sophisticated cybercrime, posing significant challenges to users, developers, and law enforcement alike. As real-world value permeates virtual spaces, understanding these nuanced threats is crucial for anyone stepping into this new digital frontier.

The New Gold Rush: Valuables in a Virtual World

The metaverse is evolving into a hybrid of social and transactional interaction, where users engage through avatars in computer-generated worlds. Unlike traditional video games, the money exchanged in these environments is often real, enabled by digital currencies like "crypto". This influx of real-world value has created vibrant virtual economies where users can buy, sell, and invest in virtual items, services, and properties. In some cases, virtual objects can be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, traded on real-world websites and exchanges. This financialization makes the metaverse a prime target for criminal activity.

Intrusive Data Collection: The "X-Ray-Like" Gaze of VR

Virtual reality devices collect an unprecedented volume of deeply personal and physiological data, far exceeding what traditional internet-connected devices gather. This includes:

- Physiological Data: VR headsets track eye movements, gait, head and body movements, and hand tracking. This data captures how your body reacts to virtual stimuli, offering insights into your physical and emotional states.

- Behavioral Data: VR also records how users interact within the virtual world, including reactions to challenges, tasks, and social engagements with other avatars.

This extensive data collection allows VR service providers to "know users more intimately than users may know themselves". Aggregated physiological and behavioral data can even form a "kinematic fingerprint," capable of uniquely identifying an individual with up to 60% accuracy based on their movement patterns. This blurs the line between identifying and non-identifying information.

Furthermore, VR environments can act as "self-sufficing data ecosystems". Because so much contextual information (like a user's mood or the task they are performing) is collected internally within the immersive environment, providers have less need to acquire external data, simplifying analysis and allowing for broader inferences about users. For example, Oculus (now Meta) requires users to grant permission for the collection and sharing of private data, including physical movements and GPS locations, with Meta, raising concerns about intrusive big data collection linked to social media profiles.

The Illusion of Consent and Subtle Manipulation

Traditional consent mechanisms, such as text-based privacy policies, are often "futile" in VR. The sheer volume, variety, and complexity of data collected make it nearly impossible for users to fully comprehend what they are consenting to. This creates a "hidden knowledge shift," where companies gain insights far beyond what a user can fathom.

To provide a truly immersive experience, VR companies design personalization based on user data to be "unnoticeable". Phrases like "experience unique and relevant to you" in privacy policies can refer to customizations (e.g., optimal visual or aural effects) that users wouldn't consciously recognize. This is problematic because companies are incentivized to offer this unrecognizable personalization, and users are incentivized to be blind to it for the sake of immersion.

The "privacy paradox" also plays a role, where users express privacy concerns but behave differently online, partly due to a lack of awareness and understanding of the far-reaching implications of privacy risks. For instance, few would consider a VR background changing color based on their heart rate a significant privacy risk, but aggregated, such seemingly negligible data points can undermine personal autonomy and self-determination.

Moreover, the high velocity of VR data, enabling real-time processing, facilitates new techniques of "subtle psychological persuasions". Companies can identify and respond to (or even proactively create) users' subconscious emotional states and vulnerabilities to influence behavior, such as through targeted advertisements or environmental atmospherics. This capacity to shape user identity without their recognition fundamentally challenges the rights to self-determination and autonomy.

The Rising Tide of Cybercrime in the Metaverse

The financial value and social immersion within the metaverse make it a lucrative target for various forms of cybercrime, directly impacting user privacy and security:

- Virtual Identity Theft: Cybercriminals steal avatars, credentials, and personal data to gain control of user profiles and impersonate individuals to commit financial fraud. Losing access to a virtual identity means losing control over assets, interactions, and personal security.

- Deep Fake Impersonation: AI-generated avatars and voice technology can mimic trusted individuals (like executives or public figures) with high realism, making deception almost impossible to detect without advanced security measures. This can lead to fraudulent transactions or the extraction of sensitive information.

- Marketplace Fraud: Cybercriminals create fake stores, fraudulent NFTs, and manipulate transactions, tricking users into spending cryptocurrency or valuable assets on non-existent goods.

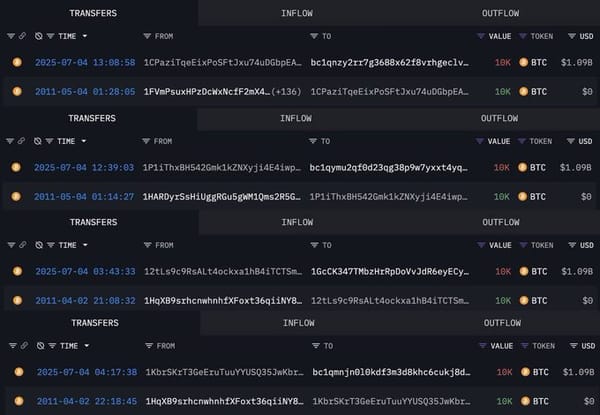

- NFT Theft: Attackers exploit vulnerabilities in smart contracts, often by getting users to sign partial contracts that are then completed to transfer ownership without payment, leading to millions in losses.

- Rug-pulling schemes involve attackers posing as NFT creators, soliciting funds from investors, and then abandoning projects while retaining the funds.

- Social Engineering: In immersive VR settings, users can be more psychologically vulnerable, making them easier targets for manipulation and fraud. Hackers exploit trust-based interactions to deceive victims into handing over digital assets, access credentials, or financial data.

- Ransomware-style Attacks: Entire VR spaces can be held hostage, with attackers demanding cryptocurrency payments to restore access, putting virtual land owners and businesses at risk of losing valuable assets.

- Corporate Espionage: Fraudsters can infiltrate virtual meetings and office environments using social engineering tactics to eavesdrop on sensitive conversations or steal confidential business information, especially as companies embrace VR workspaces.

Crypto, in general, is credited with significantly increasing internet fraud, with billions of dollars lost to scams between early 2021 and early 2022 alone.

Regulatory Lags and Limited Recourse

A significant challenge in combating these crimes is the lack of unified security standards across different metaverse platforms and the absence of clear legal regulation. Existing laws often struggle to fit virtual crimes, particularly regarding the theft of virtual goods with real-world value, leading to limited recourse for victims.

- Jurisdictional Complexity: The metaverse spans various geographies and jurisdictions, complicating law enforcement efforts due to uncertainties about applicable national laws.

- Anonymity: The anonymity of avatar owners and the difficulty in compelling service providers to suspend accounts or remove content further complicate responses to crimes like defamation or impersonation.

- Theft of Virtual Assets: It's often unclear whether the theft of metaverse assets constitutes a property crime under existing laws. While some countries like the Netherlands and South Korea have prosecuted individuals for stealing virtual goods, the U.S. has less case law in this area.

- Intellectual Property Challenges: When an NFT is stolen, the original purchaser may not have any rights to the underlying intellectual property (like copyright or trademark), as NFT transactions typically only transfer the token itself, not IP rights. This can bar victims from seeking restitution. Smart contracts, being code-based, do not function as legally binding agreements, making IP licensing difficult to enforce.

- National Stolen Property Act (NSPA): While the NSPA could potentially apply to intangible assets like NFTs if they hold clear economic value and cross state/international borders, courts have been reluctant to navigate the complexities, and identifying perpetrators in decentralized systems remains a challenge.

Forging a Safer Virtual Future

The battle against cybercrime in the metaverse is just beginning, and security measures are dangerously behind. To safeguard digital identities, financial transactions, and corporate data, a multi-faceted approach is needed:

- Advanced Security Technologies:

- AI-powered security avatars can act as real-time digital monitors, identifying fraudulent interactions, impersonation scams, and deep fake avatars.

- Blockchain can enhance security through decentralized identity verification, securing transactions and digital assets, and preventing fraudulent NFT sales and unauthorized financial transfers.

- End-to-end encryption for VR communication is essential to protect voice chats, meetings, and private exchanges from interception.

- Digital forensics for AI-generated manipulation is an emerging field developing tools to differentiate between legitimate users and AI-driven impostors.

- Smart contract audits can help identify vulnerabilities before deployment, though they are not foolproof and new risks can emerge post-publication.

- Rethinking Consent and User Education:

- Moving beyond "futile" text-based consent, VR companies should offer customizable privacy settings allowing users to control the extent of physiological data permitted for their immersive experience.

- Complementing settings, interactive educational tools (e.g., short videos, quizzes) prior to VR use can help users comprehend the far-reaching implications of data collection and counter the "privacy paradox".

- Regulatory Evolution: Clearer legal guidelines are needed to define what constitutes a crime in the metaverse, what data can be collected by lawful interception, and what operators' obligations are to cooperate with law enforcement. The Biden administration has released a framework to aid lawmakers in regulating digital assets, encouraging Congressional intervention to address cybercrime and potential gaps in existing laws.

- Industry and Community Collaboration: Gaming companies need to communicate more with law enforcement and provide resources for investigations. Parents also play a critical role, needing to be aware of the virtual environments their children inhabit, understand vulnerabilities, and maintain open dialogue.

As virtual worlds expand and real-world value in crypto and NFTs continues to grow, cybersecurity must adapt just as rapidly. In the metaverse, trust is the most valuable currency, and criminals are already exploiting it. Ensuring its responsible development and user protection will require continuous innovation, robust legal frameworks, and a collective commitment to safety and privacy in this exciting, yet challenging, digital frontier.